- Home

- Steve Howell

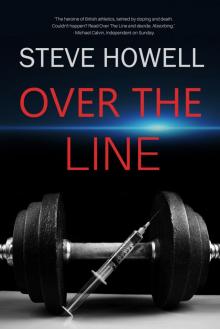

Over the Line

Over the Line Read online

Over The Line

Steve Howell

Published by Accent Press Ltd 2018

www.accentpress.co.uk

Copyright © Steve Howell 2018

The right of Steve Howell to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by the author in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

The story contained within this book is a work of fiction. Names and characters are the product of the author’s imagination and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the written permission of Accent Press Ltd.

ISBN 9781786156259

eISBN 9781786156266

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Clays Ltd, St Ives plc

“What I know most surely about morality and the duty of man I owe to sport.”

Albert Camus

1

The Trial

On most days, the crowd at an athletics meeting would barely fill a bus. We huddle in half empty stands, at out of the way tracks, almost unnoticed. But this wasn’t most days: access roads had been gridlocked for hours, the stadium was teeming with expectation, and I was struggling to find my seat somewhere in the section facing back down the home straight to the start.

As I edged my way along a row, people half-stood or wriggled sideways to let me shuffle through. I had a few nods of recognition – familiar faces I’d seen around the athletics scene over the years – but I was relieved that there was no one nearby I knew well. I was in no mood for small talk.

I had left Megan in the warm-up area. I don’t crowd my athletes on the day of a race. I’ll watch them warming up for a few minutes, I’ll check they’re okay, but I don’t give them last-minute advice. Not unless they ask for it. I reckon it’s too late by then for me to make any difference – the work’s been done, and it’s all about execution. You have to let them get on with it. Trust them.

Megan had gone through her routine of stretching and striding. There was nothing especially abnormal about her manner, no obvious signs of tension or trouble. As usual, she kept her side of the conversation to one syllable at a time. She was feeling “good”. The windy conditions were “a pain”. And “yes”, she had stretched her dodgy hamstring.

I squeezed into my seat and looked around the stadium. On the track, marshals checked the hurdles, making sure lines were straight and heights were right. On a platform beyond the finish line, photographers jostled for position, lining their lenses up like a firing squad. In the stands, all the aisles were peppered with people hurrying to their seats, clutching bags and bottles. This race had been hyped as the highlight of the day, and no one wanted to miss it.

To my left, a man heading for obesity was working his way through the contents of a giant lunchbox, elbowing me as he shovelled food into his mouth. Much to my relief, the woman to my right was leaner, but I still had to hunch my shoulders as I sat between them.

“It’s Megan Tomos in this one,” the lady announced in my general direction, with more than a hint of a Brummie accent.

I kept my reaction to a nod, not wanting to encourage her. I take my coaching seriously – my ex-wife would say too seriously – and, at that moment, with all I’ve worked for on the line in more ways than one, I didn’t need any distractions. I wanted to watch Megan even more closely than usual.

“I’ve been looking forward to it,” she said. Obviously, the nod was too much encouragement. “I think she’ll do well in Rio.” She paused for a moment, gazing into the distance as if imagining Megan with a gold medal round her neck. “I saw her on TV a week ago,” she continued, turning back to me, undeterred by my silence. “You know, the Diamond League in Rome? Wow! She won it comfortably – beat the Americans. Super run. Nice girl. They interviewed her afterwards, and she seemed so lovely. Oh, here they come.”

The athletes were emerging from a tunnel and turning onto a pathway at the foot of the main stand, heading for the start area. Each athlete was paired with a steward clutching a bright yellow container for their kit. Megan was halfway back. She was the fastest qualifier for the final, and that put her in Lane 4. A wave of enthusiastic applause was following her.

I pulled my specs out. I’m still in denial about needing them, but this was no time for vanity. I squinted through the lenses at Megan’s broad shoulders, checking again for warning signs. It was hard to tell, but she seemed rigid and tense, and she wasn’t responding to the crowd or walking in her usual, half-skipping way.

I pulled my phone out, shoved my glasses onto my forehead and flicked through the headlines. Nothing on the news pages about Megan. Nothing was good. I tapped the Twitter button and thumbed the tweets gushing in from fans, athletes, pundits and reporters. Endless mentions of #Megan, @Meg_Tomos and #Rio2016, but it all seemed harmless. That was also good.

The woman next to me suddenly seemed beside herself with excitement. “I used to do the hurdles,” she said.

Oh no – I sensed a life story coming. This time, I didn’t nod. I was trying to concentrate, watching Megan and her seven rivals arriving in the start area, peeling off tracksuits and checking their blocks. All of them began limbering up with trial starts, the momentum carrying them over the first couple of hurdles. Megan’s hurdling was as smooth as ever, like the obstacles hardly existed.

“She’ll win this easily,” the woman said, undeterred by my silence. “Ten metres. I’d give her ten metres on everyone else. There’s no one to touch her.”

She was stating the obvious. Of course Megan should win. “But it’s an Olympic trial – anything can happen,” I said, trying to make it sound like the last word.

The woman nudged me. “She doesn’t look very happy,” she said, nodding towards the far end of the stadium.

My eyes darted up to a huge screen above the start. The athletes were lining up now, and the camera crew was in Megan’s lane, zoomed-in on her grim face. The commentator was introducing her, babbling about her being the world leader and British record holder and “our big hope for Rio”.

I discouraged my athletes from showing-off for the cameras, but Megan would normally have given the crowd a warm smile and a two-handed wave. But her arms remained fixed at her side. She was staring into the camera like she was oblivious to the frantic cheering around her. My unease was growing.

The starter told the athletes to take their marks. I knew him well. He was old school and very particular. He held them in the set position for far too long, until one of the athletes jumped the gun, and everyone followed her. The starter fired two shots in quick succession to call them back. Some pulled-up before the first hurdles, others clattered through them. Megan only took a couple of strides. The camera focused on her again as she walked back. She looked even grimmer now, shaking her head as the ground staff tidied up the hurdles.

The athletes settled into their blocks for the second time. The re-start was clean. But Megan was slow to get away. She was last to rise at the first hurdle and still trailing at the second. My hands were clenched, sweat gathering in my palms. The woman next to me was rigid and, mercifully, silent. But Megan didn’t panic. In that split second, the years of work shone through. She clicked into gear like a machine, perfectly balanced, immaculate technique. And by the sixth hurdle, she was surging past the others, making them look like the parents race at a school sports day.

The whole stadium was on its feet. Some fans were waving ‘Leg it Meg’ placards. The commentator screamed, “Megan Tomos – That Was Awesome!” The man to my left nearly choked on a sandwich. The woman next to

me was beside herself, jumping up and down, looking alarmingly like she might hug me.

“Did you see that?” she screamed. “My God, that was fantastic. What a super run.”

I smiled and nodded but only from politeness and a large dollop of relief. It was a good recovery, but not super or fantastic – not by Megan’s standards.

Momentum had carried her twenty or thirty yards beyond the finish line now, and as usual, she was bent with her hands on her knees looking up at one of the screens. As the results came up confirming her victory, she straightened, turned and started walking briskly across the track.

The other athletes were offering hands, hugs, and nods of respect. But Megan brushed them away and marched off the track, head down, ignoring cheers and shouts from the crowd, sweeping past the photographers and TV interviewers. One of the photographers darted towards the entrance to the tunnel, blocking her way, trying to take a picture of her face. I felt a sickening pulse of anxiety shooting through me, a sense of helplessness, as he raised his lens and she lifted an arm across her face, and then he stepped closer, and she swept her arm towards him like she was swatting him away, knocking the camera from his hands.

The photographer fell forward trying to catch his camera, hitting the ground face first, as Megan stepped sideways over one of his splayed legs and disappeared into the darkness.

The crowd released a collective gasp, which hung in the air and then floated away, leaving an uncomfortable silence. People seemed frozen for several moments, unsure of what to make of what they’d seen, or how to react to it.

Gradually, disconnected murmuring grew into a buzz of animated conversation like an orchestra warming up. I was too stunned to take in anything that was being said around me. The lady next to me had slumped into her seat without a word, her excitement punctured, but I remained on my feet, staring at the tunnel entrance, my last glimpse of Megan’s back disappearing into the darkness still fixed in my mind.

I started to leave, giving a polite nod to the lady, who now seemed like a rare friend in a crowd that, I could see, felt bewildered and let down. I edged along the row, even more thankful no one seemed to know I was Meg’s coach. On reaching the exit, I took a final look across at the photographer. He was making a bit of a show of dusting himself down, lapping up the solidarity of the fellow snappers who’d gathered around him.

I checked my watch. Megan and I had a press conference in half an hour.

2

The Tweet

It was never going to be an easy week. The Olympic trials are like a trip-wire set in the path of the best athletes. Eager rivals love to bring down the big names, everyone wanting the automatic place set aside for the winner, everyone’s nerves twitching. There were bound to be unexpected problems: the nasty surprises you know are possible – a late injury, a stomach bug, a stumble at a hurdle. But what had happened on Thursday, three days before the trials, was something not remotely on my radar, and it threatened Megan’s Rio ambitions and everything and everyone revolving around them – me included.

I was in the library at Middlesex University marking exam papers. My day job is teaching sports science, but my employer cuts me some slack for coaching Megan, and that includes taking several calls a day from Mimi Jacobs. Mimi does the PR, and she’s permanently on a mission to embroil me in building Meg’s personal ‘brand’. Give me a break.

I was toying with not answering this call. When the phone started vibrating and moving sideways across the desk, I stared at Mimi’s name for a second, wondering if it was going to be about meeting for lunch. Lately, nothing was too unimportant to warrant a pow-wow at a coffee shop she’d adopted in Hendon Central. “It’ll only take ten for me on the tube,” she’d say, practically heading for Belsize Park with her Oyster card ready before I could answer.

I wanted to finish my marking, but it was too close to the trials to ignore a Mimi call.

“Liam!” she said urgently, when I answered. “Have you seen the tweet?”

“Hang on,” I said, walking briskly towards the exit, sensing a few dozen exam-weary eyes glaring at me.

Mimi sighed impatiently. “Liam, are you listening?” she said. “There’s a tweet you must read.”

I nearly laughed out loud – or should I say LOL-ed. I’m not into Twitter. Not at all. All that self-obsession is very irritating – but it’s become part of the job. I don’t tweet myself, but I do follow all Megan’s rivals to gather snippets about how they’re doing, what their plans are, what they’re boasting about. It’s surprising how much they give away.

“What tweet?” I said, now outside and hunting for some shade.

“It’s about Meg,” she said, “and it could be really damaging.”

I decided to head for The Quad, which had coffee and chairs as well as shade.

“Do I need to be sitting down for this?” I said, trying to sound ironic. Mimi is easy to wind up.

“Liam,” she said. “This is serious. Meg has an old boyfriend who’s connected in some way to the death of another boy. They all went to school together. And it was a drugs overdose – he died of a drugs overdose.”

That got my attention. “What do you mean? Like heroin or something? Read it to me”.

“I’ve emailed it,” she said.

“Hang on.” I was fumbling with my phone, trying to get into my emails without cutting Mimi off.

The top one was headed @Will2Play and a tweet was pasted in it saying ‘Make all the crazy threats you like but leave Meg out of it.’

I was in The Quad now heading for a chair in the darkest corner, away from the glare coming through the glass roof. As I sat down, I read the tweet through again.

“Liam?” Mimi said, sounding not sure if I was still there.

“Leave Meg out of what?” I said in a whisper, conscious some of the people around were sports science students who knew I coached Meg and invested way too much time in sucking-up to me in the hope of getting an introduction. “I don’t get it. What crazy threats?”

“I don’t know,” Mimi said. “It’s something to do with the police re-opening an investigation into this boy’s death.”

“Death?” I said. “When did this happen?”

“About two-and-a-half years ago.”

“Two-and-a-half years,” I repeated, stunned that it must have been around the time Megan had turned up at Copthall Stadium, my local track in north London, a nervous nineteen-year-old looking for a new coach and – I later found out – scared I might say ‘no’.

I allowed myself an inward smile whenever that thought came to me. It seemed so ridiculous now, with Megan so close to achieving the ultimate prize in sport, but even then there was no way I would have turned her down. I did have a waiting list of sorts, but she was already being talked of as another Jessica Ennis and any coach’s dream opportunity.

“How did you find this tweet?” I said. “Are you sure he’s talking about our Meg?”

There was a pause, like Mimi was trying to summon the patience to explain the alphabet to a moron. “Liam, darling, he is talking about our Meg,” she said. “Do you think I’d phone if I wasn’t sure?”

“You’ve phoned me for less,” I said, regretting it almost as the words were coming out. I sensed Mimi recoil at the other end of the line.

“Look, I’ve had a call from the Argus, the local rag in Newport.” Mimi sounded hurt or annoyed, or both. “Stuff about Megan can’t be put on Twitter without a journalist spotting it or someone tipping them off. The reporter was asking questions about Meg’s relationship with Will and lacing it heavily with references to the other boy’s death being drug related.”

“What relationship though?” I said, feeling a rising sense of anxiety, knowing how the ‘D-word’ – regardless what type of drug – would send Megan’s sponsors into a panic. “I mean, I’ve never heard of Will. Surely she’d have mentioned him if they were still in touch? It doesn’t make sense. She barely has time for Tom, never mind another man.”

&

nbsp; “I know,” Mimi said. “I can’t get my head round it either, and the guy wasn’t giving much away. But it sounds like Meg was dating this Will for ages. Childhood sweetheart. Back of the bicycle shed and all that… And now he’s in some kind of trouble.”

“How much trouble?” I said.

“It sounds like the parents of the boy who died – Matt he’s called – won’t let it go. They weren’t happy with the original police investigation, and now it’s been reopened and Meg’s ‘ex’ is in the firing line. I’m not sure why. I was trying to fob the journalist off. I didn’t want to sound that interested. But we’re going to have to ask Meg what it’s all about. The journalist wants a comment, and I need to get back to him with something.”

“No you don’t,” I said, more abruptly than I intended. “No way. I don’t want her being bothered just before the trials.”

“But Liam...”

“Wait until Sunday’s out of the way.”

Mimi sighed. “Look,” she said, “the media don’t give a toss about Olympic trials. They have their own agenda, and the Argus could run a piece any day. Then the nationals will pick it up, and before you know it… Okay, I think this guy was just fishing, but I don’t know for sure what he knows, or what it’s all about, and I don’t like not knowing. We need to talk to Megan.”

I read the tweet again. What was @Will2Play up to? Why mention Meg’s name if you want to keep her out of it?

“Liam?”

“Okay, I take your point,” I said. “There’s a possibility the journalist could run a story anyway. But why guarantee it by feeding him a comment? Let’s sit tight. If he’s got something, he’ll run it. If Meg goes mad because we haven’t warned her, you can blame me. I’ll take a chance on it. Let’s just keep a close eye on her. We know her well enough to know if there’s something on her mind.”

“We could talk to Tom?”

I sensed Mimi knew this was a stupid idea even as the words left her mouth. Tom – a moderately successful 800m runner – had been living with Megan for about three months, having followed her around like a groupie for the best part of a year. You could see why she might have succumbed to his Viking-like looks, but it was hard to spot any other grounds for attraction.

Over the Line

Over the Line